Seeing Stars - Inverness Courier, Friday 6th April, 2007

Light and Shade

By Antony McEwan, Highlands Astronomical Society

In April, the traditional dark sky observing season begins to draw to a close. We are now officially in British Summer Time and the Sun sets that much later, giving us the beautiful long sunsets that mark warmer and lighter times ahead. It’s not the end of the world though, as there are still several hours of true darkness to be enjoyed, even at the end of the month, and true darkness is not required at all to enjoy some of the very best sights the sky has to offer.

If you still hunger to see faint astronomical targets in the hours of darkness, then the constellation of Leo is climbing high in the southwest now, and bringing with it a huge collection of galaxies that can be seen with even small telescopes. Leo is placed well away from the Milky Way, which represents the plane of our own galaxy. When we look at Leo, we are looking through a much more relatively dust-free part of space and seeing galaxies and other objects that are much further away than a lot that we see in other constellations.

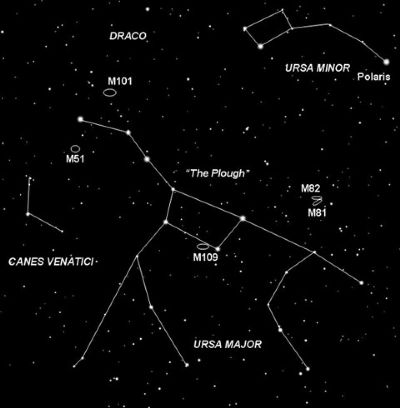

Ursa Major, the Great Bear, is also well placed at the moment. Being circumpolar, the constellation rotates around the pole star Polaris and never gets low enough to go below our horizon. This does mean though that the angle of the constellation in the sky changes through the seasons. This month the ‘handle’ of the big dipper asterism in the constellation is almost directly overhead, which can be a little disconcerting if you haven’t observed it for a while! Ursa Major is also a fine repository of galaxies for the spring-time enthusiast, including many of those included in Charles Messier’s list; M81 and M82 are a particularly attractive pair of spiral galaxies that can be spotted in even 3” aperture telescopes. Other more challenging ones include M101 and M51, the latter consisting of a pair of galaxies, one of which is pulling material away from its companion! Amazingly, the ‘bridge’ of leeched material can be seen from Earth in moderately sized telescopes!

Spring offers advantages for observers who don’t want to contend with the cold temperatures of winter nights too. It doesn’t have to be dark to observe three excellent targets this month: The Moon, Venus and Saturn. They are all so bright that they can be found even against the glare of dusk, and the Moon can easily be observed during proper daytime too, particularly when it is past ‘full’ and waning towards last quarter, when it rises in the early hours and can be seen until late morning.

Most lunar observing is done in the time between New Moon and Full Moon. As the shadow terminator spreads across the lunar face, we are able to see the craters, mountain ranges and marea bisected by the line of shadow that represents the extent of the Sun’s illumination. As the Moon’s phase becomes more full, the light plays differently on its surface and features can change appearance markedly as their illumination becomes more face-on. Once the Moon is full, and it begins to wane, the light changes even more dramatically. Sometimes it can appear to be a completely different colour, having a yellowish tinge compared with the whiter light during the waxing period of the lunation. Also, because the features are being illuminated from a different side, the effect on how they appear can be quite dramatic, as you get a different perspective on otherwise familiar features if you have not observed them during the waning period before.

Venus is easily seen in the northwest after Sunset, and is the brightest object in the sky, after the Sun and Moon. Because Venus orbits closer to the Sun than we do, it is called an ‘inferior’ planet – its orbit is inside ours – and this also means it shows a phase like the Moon does. We can see Venus being illuminated nearly face on by the Sun, when it is on the Sun’s far side, or we can see it closer to us than the Sun, when it will show less of its illuminated face to us, and can be obviously crescent-like. Telescopically Venus doesn’t show us much, as it is covered with a very dense, cloudy atmosphere, but it can still be interesting to follow its phases as it completes an orbit of the Sun.

Saturn on the other hand is a superior planet. It is much further away from the Sun than we are, so its orbit is outside ours. It is very easy to find just now, shining brightly ahead of the Sickle asterism in Leo. The effect of light can be seen when observing this planet too. Saturn’s ring system extends all around the planet, and so the planet itself can cast a shadow onto the rings behind it. Also, where the rings pass between the Sun and the planet itself, they can also cast a shadow onto the globe. Both of these effects can be seen in small telescopes, and it can be immensely rewarding trying to detect the slight changes in these shadow shows as the planet’s position changes relative to the Sun and ourselves. Yes, it’s great to see the rings in themselves, but seeing the subtle effects of the play of light can give a very strong sense of depth to your observations of the ringed planet.

We sometimes mourn the passing of the dark winter nights, thinking that we are losing out to the advance of evening light, but there is still plenty to see, and in less harsh conditions too. It’s all just a matter of perspective and being able to accept the views we have rather than bemoaning the ones we can’t see anymore. And besides, there’s always next winter…