Seeing Stars - Inverness Courier, Fri 5th Nov, 2010

Getting your Goat: the constellation Capricornus

By Pat Williams - Highlands Astronomical Society

An interesting, and sometimes overlooked constellation in November’s sky, is Capricornus (pronounced kap ri kor nus), the sea-goat, named after the Greek God Pan. As with all mythological tales there are various versions as to how the constellation came by its name. One that is widely accepted is that in order to escape the rampage of the titanic demon Typhon, at Pan’s warning shriek, the gods metamorphosed into animal forms and jumped into the river. Hence the term panic. While on land Pan was a goat but when he jumped into the water his lower half became a fish’s tail.

Surfacing, he blew on his pipes a note of such excruciating pitch that it drove the demon away, saving the injured Zeus. His reward was to be placed in the sky in his sea-goat form, making this the first recorded piping trophy. If you go down to the woods today (or any other day) and look north on Culloden Drive you will see Iain Chalmers’ beautiful tree sculpture of Pan showing all these features.

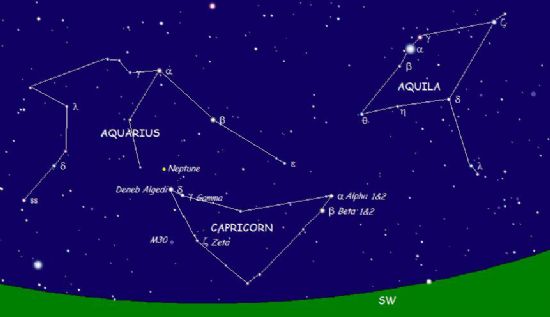

The constellation of Capricornus is visible to us in the Highlands all through November, low on the southern horizon. If you go out on a clear night at as it gets dark and look south, you should see it clearly between Aquarius and Aquilla. The diagram shows how its shape could be that of Pan with his head to the East and curled up tail to the West. Inversely, the Australians think it resembles a kangaroo.

In the 2,600 years since the Tropic of Capricorn got its name, the Winter Solstice has moved from Capricornus to Sagittarius because of precession. At the solstice, the shortest day in the northern hemisphere, the sun is overhead at 12 noon at the Tropic of Capricorn. That is the furthest south in any year that the sun travels.

The 31 visible stars in Capricornus, with one exception, are no brighter than 3rd magnitude, but the constellation is easily recognised. The brightest star lies in its northerly aspect. Delta Capricorni A, a star named Deneb Algedi, shines at magnitude 2.85, easily visible to the naked eye. It is 38 light-years away from the Sun and is an eclipsing binary with Delta Capricorni B, with its magnitude dropping by 0.2 during an eclipse. Delta Capricorni is in fact a four star or quaternary system with C and D components being one and two arc minutes away respectively. The next brightest star is Beta Capricorni. This is a double star over 20 degrees west of Deneb Algedi. At magnitude 3.5 Beta 1 Capricorn, Dabih, is the brighter of the double stars and is 344 light years away. Beta 2 Capricorni is magnitude 6.09 and 313 light years away. With binoculars it is possible to resolve the two stars, which are separated by three and a half arc minutes.

Alpha 1 and 2 Capricorni are another pair of double stars. Their apparent proximity is created by our line of sight from Earth. The two stars are actually hundreds of light years apart but each is also a true binary with a faint companion of its own visible even at low magnification. Alpha 1 is magnitude 4.3, yellow-orange in colour and 686 light years away. Alpha 2 or Algedi is magnitude 3.58, golden yellow and 108 light years away. The pair lie about two degrees above Beta Capricorni. They have a separation of 6 arc minutes and are a good naked-eye test for a night’s “seeing”; that is, how clear and steady the atmosphere is. Nashira is magnitude 3.69 and two degrees from Deneb Algedi, and six-and-a-half degrees to the Southwest, Zeta Capricorni shines at magnitude 3.77.

Thousands of light-years away from the Sun and still in Capricornus lies the beautiful globular star cluster M30. This is found by star hopping three degrees east from Zeta Capricorni. At magnitude 7.5 it spans 12 arc minutes across, can be seen as a fuzzy patch in binoculars, and is a beautiful sight even in a small telescope.

Looking towards Capricornus on September 23rd 1846, Johann Galle, at the Berlin Observatory, discovered Neptune. Today’s 21st century astronomers have found over 300 planets circling stars other than our Sun but the first deliberate search for a planet was undertaken in the 19th century. Uranus, the seventh planet in our solar system, had minor discrepancies in its orbit, in that it sped up and slowed down. The presence of an eighth planet would explain this. So, the existence of Neptune was predicted before it was seen. French mathematician Urbain Le Verrier working with pen and paper and, using Newton’s Laws of Motion, calculated where the planet would be found. Such was the accuracy of the calculations that it took Galle only 30 minutes to do so. This is justly famed as a triumph of reason, hard work and the brilliant application of celestial mechanics. John Couch Adams, an English mathematician made the same calculations a year earlier but his work was ignored by English astronomers. In 1998 papers were found which showed that Adams’ work was less accurate than Le Verrier’s was anyway.

As with all constellations close to the ecliptic, the planets, Sun and Moon will pass regularly through Capricornus. Until 2011 when it moves into Aquarius, Neptune is once again in Capricornus, and can be seen east of the goat’s horns. It is possible during November to see the planet with binoculars, with difficulty, or with more ease through a small telescope. At opposition (the position of the planet when it is opposite the sun in the sky), which occurred on 20th August 2010, Neptune’s brightness was magnitude 7.7. With a clear, dark sky the dark-adapted unaided eye can see up to magnitude 6.

On 5th November, fireworks night, the celestial skies will compete with the earth to dazzle us with power. Look high to the East to see meteors and the occasional fireball from the Taurid meteor shower. If the skies are clear, they will compete with earthly fireworks at a rate of 7 per hour. The sky should be dark for both fireworks and fireballs with the new Moon not due until the 6th.