Seeing Stars - Inverness Courier, Fri 6th Nov 2009

Ride The Winged Horse

By Antony McEwan - Highlands Astronomical Society

As a child, did you ever dream of flying? Perhaps on a magical winged horse? Soaring above the Earth in search of adventure, or perhaps playing the part of a protagonist in a great epic tale?

Winged horses, or Pegasi, are popular in mythology and fantasy. Horses are common beasts, used for many purposes by people through the ages, and yet the addition of a set of magical wings transforms them into something much more – lifts them above the mundaneness of everyday life perhaps. No wonder they appeal to the imagination of the masses.

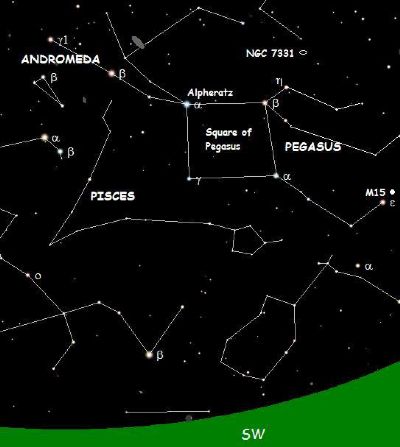

The constellation of Pegasus, the winged horse of Greek mythology, is now high in our south-western sky by mid evening in November. The constellation is very large, and the main body is formed by a square of stars. Consider this the body of Pegasus. Extending down from the body, the line of Zeta (Homam) and Theta (Baham) Pegasi represent his neck and Epsilon his nose. Seen from the Northern Hemisphere, Pegasus is quite evidently flying along on his back. I suppose he’s entitled to show off a little, seeing as he is supposed to be a magical creature, offspring of the god Poseidon and the Gorgon, Medusa.

For amateur astronomers with small to medium aperture telescopes, there is not a lot contained within the square of Pegasus that warrants looking at. There is, however, something wonderful outside the square but within the constellation that very much deserves observation, and that is M15, a fantastic globular cluster.

The cluster is reckoned to be over 13 billion years old, making it one of the oldest globular clusters known. The age of the universe is thought to be between 13.5 and 14 billion years, so you can see that M15 is something that has been around most of the time the universe has been in existence. It is 33.6 thousand light-years away and is thought to be the most densely populated cluster in the Milky Way. It contains a very large number of variable stars too. These are stars whose brightness as seen from Earth changes, whether it be caused by a physical change in the star, or by the star being occulted or eclipsed periodically.

M15 contains 112 such stars, but bear in mind that it is not easy to resolve the cluster into individual stars with everyday equipment. Binoculars will show the cluster as a soft fuzzy glow. A small 3-inch refractor will give a slightly brighter fuzzy glow. A good 6-inch reflector will begin to resolve the outermost stars into individual points of light and will show the central core as a softly glowing orb, unresolvable. An 8-inch will show slightly more detail, and with every increase in aperture used the view will become more and more attractive.

There is plenty to keep us interested in M15, as the central core (the bit you can’t resolve into individual stars with small or medium telescopes) has collapsed in on itself at some point. This could be because of the gravity of a large number of stars acting upon each other, or it could be because of the existence of a dense, supermassive object at its centre – possibly a Black Hole. It is not known for sure yet what caused the collapse, but if it is a Black Hole then it is ideally placed for extended study. M15 is relatively close to us and is in a portion of the sky that has little matter occupying the space between it and us so the ‘view’ is quite clear.

For lovers of deep sky objects, there is a galaxy of note within Pegasus, that being NGC7331. It is not an easy target; at magnitude 10.4 it is technically within reach of small telescopes, but as with all galaxies larger apertures will give you much more rewarding views. The galaxy is known as the Milky Way’s Twin, because its size and structure is so similar to our own galaxy. NGC7331 has a mystery associated with it. Galaxies of this type are constructed like two fried eggs slapped together, with a large flat halo and a round bulge at the centre. Normally, the bulge rotates in the same direction as the galaxy’s halo, but in 7331’s case it revolves in the opposite direction! Why? Nobody knows for sure, but it’s thought that the central bulge may contain material that has ‘fallen into’ it because of gravity.

Interestingly, the star Delta Pegasi (known as Alpheratz or Sirrah) is also shared by the constellation Andromeda, and although it has the designation Alpha Andromedae, it is not the brightest star in that constellation as Beta is almost identical in brightness. Alpheratz is a binary system, meaning that it consists of two stars in close orbit around each other. Although this does mean that the star is slightly variable, it is so only to a very minor extent, with the difference in detectable brightness being recorded at only a tenth of a magnitude.

Sadly, you will not be able to see the companion star visually. It is thought to be about a tenth as bright as the primary star, and can only be detected by the use of spectroscopes, which can measure the chemical composition, physical properties, and direction of travel of astronomical objects.

So, even if only for the wonderful globular cluster M15 and for the flight of fancy that gazing at a winged horse in the sky may stir in your thoughts, Pegasus is a worthwhile constellation to have in our sky this month. The large 14-inch aperture of our computerised telescope at the Jim Savage-Lowden observatory at Culloden will no doubt be trained on M15 and NGC7331 during our public observing sessions this month, so you are welcome to come along and experience it for yourself. Also this month, on the night of the 17th you may have a chance to see the Leonid meteor shower, with up to 100 meteors per hour being predicted this year! There are no guarantees of course, but we can hope.